Life Expectancy Varies Drastically by State

A new study reveals a dramatic life expectancy gap between states. The MAHA movement won’t fix it, but public investment can.

Hi - this newsletter is free to read, but a paid subscription helps to support my work. If you find it helpful, please consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber. Thanks for being here.

Across the political spectrum, concern about America's health is mounting. Chronic illnesses are increasingly prevalent, more children are being diagnosed with conditions like diabetes, obesity, and anxiety, and life expectancy remains below where it stood a decade ago. Meanwhile, our for-profit healthcare system often prioritizes revenue over patient care, leaving millions struggling to afford basic services or burdened by medical debt. In this context, the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement has gained traction. Its promise to tackle chronic illness and clean up the food system resonated with voters eager for solutions to the country’s growing health crisis.

The Trump administration recognized that sentiment and leaned into it, launching MAHA as a sweeping public health initiative. In his inaugural address, President Trump vowed to “end the chronic disease epidemic” and “keep our children safe, healthy, and disease free.” Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. echoed those concerns, calling it a “breathtaking epidemic” and warning that the United States has “the worst health outcomes in the developed world.”

The thing is, they’re not wrong about the problem. But they are deeply misleading about the solution.

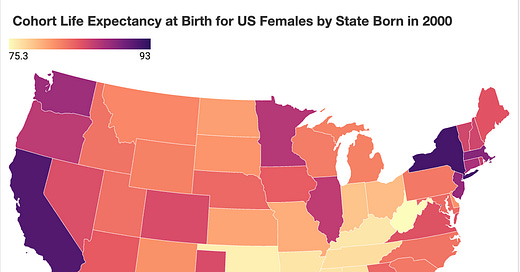

MAHA speaks of American health as if it’s a single, shared experience. As if the crisis impacts all communities equally. As if everyone is starting from the same place. But in reality, health outcomes in the United States vary dramatically depending on where you live, your income, and your race:

Life expectancy can differ by over 20 years between ZIP codes just a few miles apart. In 2020, life expectancy in Mississippi was 71.9 years, nearly a decade shorter than in Hawaii (80.7 years).

Black women in America are nearly three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.

Adults living below the federal poverty line are more than twice as likely to have diabetes compared to those with higher incomes.

Low-income Americans are 5x more likely to report poor or fair health than wealthier peers.

And yet, instead of confronting these structural inequities, the administration is actively dismantling the very tools that could help address them.

They’ve proposed cutting hundreds of billions from Medicaid and SNAP, two of the most effective public health programs in the country. They’ve canceled NIH grants focused on maternal mortality, HIV, and racial disparities in health. And they’ve banned terms like “equity,” “gender,” and “social determinants of health” in federal research proposals, erasing the language that helps us study and solve these problems.

That’s the dangerous illusion behind this movement. While it talks about improving health, it erases the realities of who is most affected, and what it actually takes to change that. You can’t fix what you refuse to name. And if we can’t talk about who’s being left behind, we’ll keep designing policies that work best for the people already experiencing the best health outcomes, while leaving those struggling the most behind.

New Study on Life Expectancy

People within the MAHA movement, including Health Secretary RFK Jr., often point to how the U.S. ranks poorly in life expectancy compared to other countries. But we actually don’t need to look abroad and compare ourselves to other countries. We can simply compare states and districts within our own borders to see staggering, persistent disparities. A new study just published in JAMA Network Open makes that painfully clear.

This analysis looked at 179 million U.S. deaths and examined how life expectancy and mortality patterns changed over the 20th century by state and birth cohort. In other words, it followed how people born in different decades, in different parts of the country, fared across their lifespans.

Researchers used national mortality and population data from 1900 to 2000 and applied an age-period-cohort model to estimate life expectancy at birth and at age 40 for each generation, alongside how quickly mortality risk doubled after age 35, which is a proxy for how fast people age, biologically and structurally.

What They Found

While life expectancy improved dramatically over the 20th century in many Northeastern and Western states, some states, particularly in the South, saw almost no improvement at all.

For women born in the year 2000, the 10 states and districts with the highest life expectancy were Washington D.C., New York, California, Massachusetts, Hawaii, New Jersey, Washington, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Oregon. In these states, life expectancy for women averaged nearly 89 years.

In contrast, the 10 states with the lowest life expectancy were West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, Indiana, and Ohio. In these states, average life expectancy for women was just under 77 years. That’s a 12-year gap. Not due to biology, but geography and policy.

The study also looked at how much life expectancy changed over the century. In the top 10 states, life expectancy for women born in 2000 increased by nearly 16 years compared to those born in 1900. But in the bottom 10 states, it increased by only 2.6 years.

In other words, women in the most advantaged states gained a full generation of life over the century. While women in the least advantaged states gained just a few years.

The takeaway is that we’re not living in one America when it comes to health. We’re living in many. And some states, often those with stronger public health systems and more progressive policy environments, are quite literally giving people decades more life.

The authors attribute these differences to a range of structural factors including public health infrastructure, access to care, tobacco control, poverty, environmental exposures, and long-term social investment.

This data exposes disparities, but it also reflects choices. In the U.S., many public health initiatives are shaped and implemented at the state level. And those state-level decisions about healthcare access, food policy, education, housing, tobacco regulation, and economic investment all play a direct role in shaping these outcomes. When the MAHA movement talks about chronic disease without addressing these drivers, or worse, works to dismantle the policies and programs that help, the result is performative health messaging with no structural backbone.

Health doesn’t just depend on individual choices. It depends on what’s around you and the systems and policies impacting those choices. And this study shows just how much those factors matter.

People are right to want change. The frustration is real, and the desire to see better health outcomes for themselves and their families is deeply justified. But that energy is being misdirected. Instead of focusing on the systems that have failed to deliver health equitably, including chronic underinvestment in public health infrastructure, disinvestment in community care, and decades of policy choices that widened income inequality and health disparities, too many are being told the problem lies with the science itself, or with the agencies tasked with protecting it. But that’s an intentional distraction to keep people focused on a made-up boogeyman while the real drivers of poor health (poverty, corporate influence, environmental neglect, and policy failure) go unaddressed. Redirecting blame toward science and public institutions is a deliberate strategy to avoid confronting the real solutions, because those require meaningful investment in people, communities, and systems. And that runs counter to the very agenda many of these leaders are pushing.

Thanks for this important piece. Another factor: transportation infrastructure. Blue states make a tangible, positive impact on health and life expectancy by investing in zoning for walkable cities, bike lanes, public transit, and traffic calming. These things go beyond quality of life to extending it, as well, by stacking together factors like getting exercise in activities of daily life, cleaner air, less noise, more independence for kids, seniors, & the disabled, less stress & expense from driving, fewer car-involved accidents, expanded community interactions, etc. DC, Colorado, Washington, Minnesota all benefit from these investments.

Thanks for this....you did not specifically call out racism but I think it is a factor as well. I was impressed with "Under the Skin" by Linda Villarosa and "Weathering" by Arline T Geronimus.....worth a read if you have not already.